Introduction: Eyecatching’s new direction

You may have noticed that I’ve become erratic of late, for which I apologise (particularly to those of you who like structure and like to stick to it). But the fact is that what I want to say and how often I want to say it is not really something that works within a weekly timetable. In addition I’ve developed a slavish adherence to mediums that aren’t fit for purpose (I.e. podcasting where I should be blogging and vice versa). And I’ve not been enjoying self imposed deadlines.

So here is how it is going to work going forwards. “Eyecatching”with be made up of four elements.

First off is my daily Blipfoto image , which has been the core of what I do for the last (nearly) thirteen years. Without fail, a picture and a few words every day. This will be the hub of what I do and where the decent people that make up Blipfoto can hold me to account, because it is quite simply A Good Place.

Second is the Eyecatching Words blog which I hope to post frequently if not quite weekly. This is where I can let my passion for writing and photography go deeper into the things that matter to me.

Thirdly, the Eyecatching Words podcast will become something that augments the blog and which I hope in future will be a place where I bring in people for conversations about what I’ve written rather than just being the audio version of my blog.

And lastly there will be Eyecatching Extras: one-offs which could be a mixture of any of the above but which will be standalone projects. Don’t ask me what this might be about but looking back over the last fifteen months travel experiences, exhibitions, meetings with interesting people, and big events could form the core of these projects.

As ever I look forward to hearing from you about whether I am getting this right. My audience will be small but then I move (happily) through a small but meaningful world. If what I offer up impacts on even one person each time – making them smile, or think, or feel moved – I will be happy. For surely it is our biggest responsibility to touch each other’s lives in positive ways, however we do it, and hopefully to make our own lives better through doing so.

So: this week’s blog

Genius: Thomas Mann, George Watts, American Fiction and me.

It always interests me when I find a theme running through my week, particularly when it is not deliberate but something more subtle. So it was this week with three seemingly unrelated choices that converged on the theme of genius, and how often it divorces you from real life.

For the record I am not talking about myself here. I could have been a genius – I was officially labelled as such as a child, more of which later – but various things got in the way such as my working class origins, my love of people and beer, childhood trauma, lack of confidence, and the fact that I couldn’t be arsed to work hard at anything or bring my enormous intellect into focus.

That of course is an issue for so many people in this world. We don’t just waste genius through suppressing opportunity we waste a huge amount of everyday talent. Genius is vastly overrated and if you have it you should keep quiet about it; and rather like having a magical power you should use it carefully and anonymously. But very few people come anywhere close to achieving their full potential because they are told from an early age that they are expected to be something other than what they hope to be. In fact they are discouraged even from hoping. The broad base of talent therefore gets lost between the twin prongs of genius and mediocrity.

Which brings us to Thomas Mann as described in the novel The Magician by Colm Toibin. I read the first chapter of this book a year ago and then I lost it and couldn’t find it. Recently it emerged from some unlikely place when I was cleaning – I can’t remember where but it was probably at the back of a shoe cupboard or under some cat bedding knowing us – so I picked it up again and have been avidly reading it for the last week.

Now Thomas Mann was an iconic figure in German literature, a Nobel prize winner who spanned the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and witnessed two world wars and a number of huge changes in Western society. As a young man he was told he was not the clever one in the family and that he would go and work in an office whilst his older brother Heinrich went off to become a famous writer.

Most people at this point knuckle under but Thomas Mann had already been inculcated with visions of something better and by all accounts had the ego and confidence to defy the expectations of his mother and elder brother. Toibin’s novel pairs a vivid picture of a man both brilliant and lonely who had a conventional marriage and six children but also a deep and mostly unrequited desire for beautiful young men, most famously captured in Death in Venice.

Mann had a routine. Write, undisturbed, in the morning. Read, walk and see people in the afternoon. His book lined study was in many ways the epicentre of his existence, more so than any family room in the various houses he lived in. But his wife, Katia, was his other main prop. A powerful and intelligent woman, she was more than a match for Mannn’s genius and gave him a humanity, a moral compass and a degree of witty sophistication that he needed.

A genius yes. Happy? Sometimes, and often contented, more of which later. Frustrated? Definitely. Egotistical and snobbish? Yes and it haunted him, but not enough to do much about it. In fact he was obsessed with hanging on to his bourgeois lifestyle even when in exile in various countries around the world. And once the Nazis came to power in 1933 he really was an outcast from the Germany he loved, and lived in America and various European countries before his death in 1955.

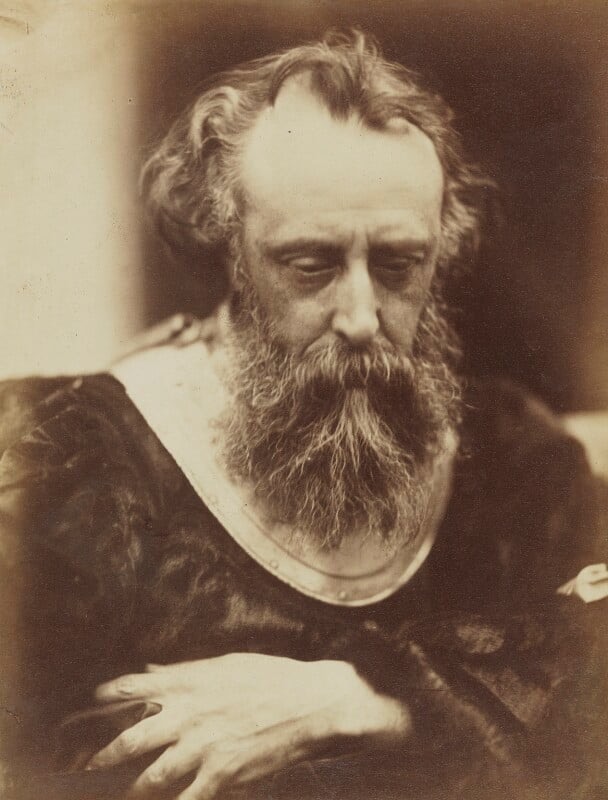

George Watts by contrast never strayed far from home. This Victorian painter of religious and patriotic subjects, and portraits and sculptures, created a life for himself in his Surrey home not far from London and for him the studio, not the study, was the most important room in the house. His exploration of the aesthetic and spiritual was also aided by being in the company of a powerful and intelligent woman in later life, Mary Fraser Tytler, whom he married when he was sixty-nine and she was thirty-six. They seemed to have complemented each other well and she bought an enormously powerful communitarian spirit to everyone who came to their home (called Limmerslea) and the nearby village of Compton.

But Watts always comes across to me as a lonely man. It is after all a lonely profession – writing and painting both require you to shut yourself away for long periods which probably explains why both professions are often associated with libidinous men (or, according to Anthony Burgess, over-enthusiastic masturbators).

Put simply genius works in isolation. When we went last week to Limmerslea and the nearby chapel, (which by the way is like something out of Lord of the Rings in its architecture), I got a strong sense of a man who painted in this world as a way of trying to enter a spiritual portal to another.

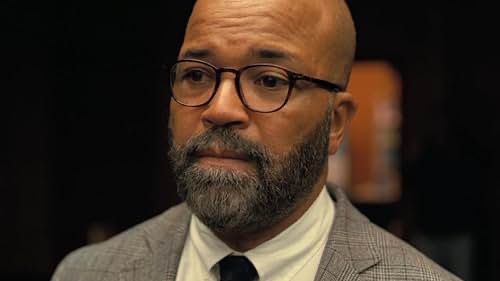

And so to American Fiction which I saw at the end of the week and which I have to say is a gem of a movie (but a cautionary word – see my reflections on Trailer Trash below). “Monk” is a middle aged black man with several good but not very commercially successful books behind him. Infuriated at the publishing industry’s expectations of what a black book should be about – namely ghetto based tales of drugs, violence and women who can’t stop getting pregnant by their dissolute men – he writes a very obvious parody of the genre. To his horror this is not only taken seriously by the white people who run the business but don’t get the joke, it actually it shoots to the top of the best seller lists and a bidding war develops over the film rights. Having branded his book with a pseudonym he is then forced to follow through and play the role of a fugitive who gives interviews on blacked-out tv screens and has to talk like one of his own characters.

Monk’s mother develops Alzheimer’s and requires an expensive care home, which feeds directly into how he manages his unexpected success with his spoof autobiography. In fact it is his mother’s remarks on genius and loneliness, uttered in a moment of lucidity despite the terrible impact of her dementia, that that for me encapsulate the whole film. He is also forced to re-evaluate his relationship with his brother and becomes involved with a woman who is central to his character development and the choices he makes later in the film.

So what is about these three things – two real people and one work of fiction – that made me dwell on the issue of genius over the course of a week? The simple answer is loneliness. In American Fiction, Monk asks his mother why she never left their father despite knowing about his several affairs. She said that he was a genius but also lonely man and that she couldn’t bring herself to leave him. In short it was the pity of a person who was being deceived towards a man who, for all his intellect, was emotionally cut off from those who wanted to love him.

I am not a genius although on a parents evening when I was about eight or nine one of my teachers told my mother that I was, in response to which she apparently rolled her eyes and muttered “not another one”. For my father was a very clever man, with all the personality challenges that bought with it, and the thought that I was from the same mould was a bittersweet idea for her. But she needn’t have worried. The opinion of a South London primary school teacher was in this case off the mark. I was not a genius and I was rescued from the remote possibility of it by the love of many good people over many good years.

I will leave the last word on this to Tolstoy. I read War and Peace many years ago and have gone back to it in various forms over the years. But there was one quote which really stuck out for me, and was chilling and probably timely. One of the central characters (Bolkonsky) lectures a younger man on women, in effect saying that if you want to achieve anything great in life you should cut yourself off from the prospect of love and marriage.

“Never, never marry, my friend. Here’s my advice to you: don’t marry until you can tell yourself that you’ve done all you could, and until you’ve stopped loving the woman you’ve chosen, until you see her clearly, otherwise you’ll be cruelly and irremediably mistaken. Marry when you’re old and good for nothing…Otherwise all that’s good and lofty in you will be lost.”

Going back to Thomas Mann – One last thing. The Magician was published in late 2021 which would have made it eligible for the next Booker prize . Having read all thirteen of the 2022 Booker long listed novels, I am astonished this was not one of them. It is, as the Guardian review noted at the time, both epic and exquisitely balanced. I would add that its dissection of the causes of dangerous populism (the rise of fascism and the impact this has on decent people) also makes it of enormous contemporary relevance, in case anyone is thinking that this is simply an old white man writing about the life of another old white man. It is not. It is a great book and for me a keeper, which is not something I say about most of the Bookers I read each year.

Trailer trash

Seeing American Fiction makes me want to write a cautionary message about film trailers. There is nothing new in what I am about to say but I have come to the view that the phenomenon of miss-selling a movie using mis-contextualised and chopped up excerpts is getting worse.

So let’s take American Fiction as a case study. The trailer I saw would have you believe it was a straight comedy, which of course is aimed at getting bums on seats. In fact much of the movie is slower and more sensitive and the pace drops and picks up at various points in the film as the narrative requires. There are at least three whole story arcs and two very significant characters that don’t appear in the trailer. It is, in short, misleading without being untrue, although to be fair the other trailer does give a different slant. Which in a way is worse. You get the trailer you want, right? I’m sure there’s an algorithm for that.

Trailer editing is, I am sure, a job in its on right in the film industry and I would bet my bottom dollar that the one for American Fiction is probably an excellent example of creating an attractive proposition for would-be cinema goers. It is very entertaining in its own right and in this day and age of What’sApp and people huddled around a smartphone screen in a bar, it is a great way to sell tickets. But it is also misleading by omission.

I share trailers for films that I think friends would like and I rarely attach a cautionary word to them. But I think I may have to start attaching caveats. Either that or I might start making videos of my own small life and present them in the form of a trailer so that people think my every day is wild and happy. Which brings me to another topic that has been much on my mind recently.

Happiness is overrated

Finally: a caution against the pursuit of happiness. I was musing on this as we left the cinema after seeing American Fiction because a key theme was to let go of anger and aspiration and recognise what is good in your life and what is happening to you now to stop you connecting with it. Stop striving for happiness and place a higher value on contentment. So I did some googling and as you would expect there is a lot of interest in this in certain quarters, particularly spiritual practices such as Buddhism and in the world of self-improvement and mindfulness.

A researcher by the name of Daniel Cordaro was working with Himalayan nomads and trying to understand whether their experience was true of other cultures in terms of emotional responses to faces. The most powerful moment came when they recognised the look not of happiness but of contentment. This came from the guide that was working with them.

“In our culture, this emotion is very special. It is the highest achievement of human well-being, and it is what the greatest enlightened masters have been writing about for thousands for years. It’s hard to translate it exactly, but the closest word is chokkshay, which is a very deep and spiritual word that means ‘the knowledge of enough.’ It basically means that right here, right now, everything is perfect as it is, regardless of what you are experiencing outside.”

Genius is rarely associated with chokkshay. Which is not to say that the two are incompatible, but that compatibility is hard to achieve. So be grateful that you are not a genius, but if you are – well, you probably need help.

That’s all for EW65. If you need a little Extra try my images from the Women in Revolt exhibition which runs for another three weeks at Tate Britain. It’s fabulous, and there is also a funny photograph of a seagull that I took. I meant I took the photograoh, not the seagull. Why would anyone kidnap a seagull?

See you next time.